Back in the 1940s, psychologists Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel conducted an experiment. They showed study participants an animated film consisting of a rectangle with an opening, plus a circle and two triangles in motion.

The participants were then asked to simply describe what they saw in the film. Before you keep reading, take a look at it yourself. I’ll be here when you come back.

So, what did you see? Out of all the study participants, only one responded with “a rectangle with an opening, plus a circle and two triangles in motion.” The rest developed elaborate stories about the simple geometric shapes.

Many participants concluded the circle and the little triangle were in love, and that the evil grey triangle was trying to harm or abduct the circle. Others went further to conclude that the blue triangle fought back against the larger triangle, allowing his love to escape back inside, where they soon rendezvoused, embraced, and lived happily ever after.

That’s pretty wild when you think about it.

The Heider-Simmel experiment became the initial basis of attribution theory, which describes how people explain the behavior of others, themselves, and also, apparently, geometric shapes on the go.

More importantly, people explain things in terms of stories. Even in situations where no story is being intentionally told, we’re telling ourselves a tale as a way to explain our experience of reality.

And yes, we tell ourselves stories about brands, products, and services. Whether you’re consciously telling a story or not, prospects are telling themselves a story about you.

Are you telling a story? And more importantly, does that story resonate with the way your prospective customers and clients are seeing things?

This is the key to knowing what your prospect needs to hear, and when they need to hear it, as part of your overall content marketing strategy. And in a networked, information-rich world where the prospects have all the power, this is your only chance to control the narrative.

What kind of story to tell?

You need to tell a Star Wars story. And by that, I mean you need to take your prospects along a content marketing version of the mythic hero’s journey.

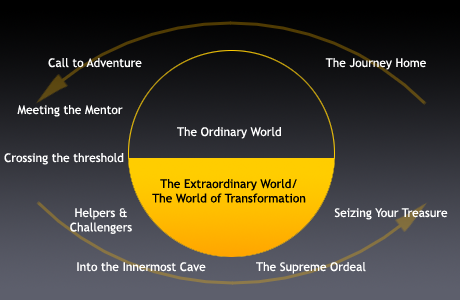

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell identifies a “monomyth” — a fundamental structure common to myths that have survived for thousands of years. Campbell’s identification of these enduring myths from disparate times and regions has inspired modern storytellers to consciously craft their work following the monomyth framework, also known as the hero’s journey.

Most notable among those inspired by the hero’s journey is George Lucas, who acknowledged Campbell’s work as the source of the plot for Star Wars. As a content marketer, you can also consciously incorporate the monomyth into your launches, funnels, and general editorial calendar.

The image above shows the general elements of the hero’s journey, which can be broken down into much more detail than presented here. It’s important to note that not all monomythic stories contain every aspect, but the original Star Wars faithfully follows almost every element of the hero’s journey.

Let’s focus on the first two steps of the journey, in the “ordinary world” before the journey truly begins. Here’s how those elements occurred in the original Star Wars.

- Luke is living in the ordinary world of his home planet, working on the family farm.

- The “call to adventure” is R2-D2’s holographic message from Princess Leia, the classic princess in distress.

- Luke initially refuses the call due to his family obligations, until his aunt and uncle are killed.

- Luke meets his mentor and guide, Obi-Wan Kenobi, who convinces Luke to proceed with his heroic journey.

- Obi-Wan gives Luke a gift that determines his destiny — his father’s lightsaber.

How does this apply to content marketing? Simple. As I mentioned last time:

Your prospect is Luke. You are Obi-Wan.

The mistake most often made in marketing is thinking of your business as the hero, resulting in egocentric messages that no one else cares about. The prospect is always the primary hero, because they are the one going on the journey — whether big or small — to solve a problem or satisfy a desire.

- The prospect starts off in the ordinary world of their lives.

- The call to adventure is an unsolved problem or unfulfilled desire.

- There’s resistance to solving that problem or satisfying the desire.

- A mentor (your brand) appears that helps them proceed with the journey.

- You deliver a gift (your content) that ultimately leads to a purchase

By making the prospect the hero, your brand also becomes a hero in the prospect’s story.

And by accepting the role of mentor with your content, your business accomplishes its goals while helping the prospect do the same. Which is how business is supposed to work, right?

8 core steps in the buyer’s journey

I’ve been using the hero’s journey to teach marketing and sales since 2007. I’ve found that just the act of thinking of the prospect as the hero makes you a better content marketer.

When you think in terms of empowering people to solve their problem by playing the role of mentor, you’re naturally performing better than competitors who take an egocentric approach.

This is also the exact way we come up with content marketing strategies for our own launches, funnels, and general editorial calendar. After years of using this strategic process, I’ve found that every buyer’s journey contains key points where you must deliver the right information at the right time to succeed at an optimal level.

Remember, each journey is tied to a particular who that you have documented. Some people create content journeys for multiple personas, but my advice is that you pick one at first and focus. Even Apple stuck with one target persona for the entirety of the Get a Mac campaign.

You’ll notice I use the word “problem” below, rather than “problem or desire.” An unfulfilled desire is a problem in the mind of the prospect, so it works on its own.

1. Ordinary World: This is the world (and worldview) that your ideal prospect lives in. She may be aware of the problem that she has, but she hasn’t yet resolved to do something about it. You understand how this person thinks, sees, feels, and behaves due to the empathy mapping process.

2. Call to Adventure: The prospect decides to take action to solve the problem. It could be a New Year’s resolution, a longstanding goal, or a problem that rears its head for the first time.

3. Resistance to the Call: At this point, the prospect starts to waver in her commitment to solving the problem. Maybe it seems too hard, too expensive, too time consuming, or simply too impractical. As we’ll discuss in a bit, this is a key content inflection point.

4. The Mentor and the Gift: This is the point that you are initially accepted as a mentor that guides the buyer’s journey. The prospect accepts your offer of a gift, in the form of information, that promises to help her solve the problem.

5. Crossing the Threshold: This is the point of purchase where the prospect believes that your product or service will lead to the problem being solved, which will lead to transformation. The most important thing to understand is that, unlike flawed funnel metaphors, the journey does not end at purchase.

6. Traveling the Road: The customer begins using the product or service with the goal of achieving success in the context of the problem. Who cares if the customer stops the journey right after purchase, right? Wrong — too often this leads to a refund request; plus you miss out on the huge benefits that accompany a happy customer.

7. Seizing the Treasure: The customer experiences success with your product or service. What does this look like for them and you? How will you know when it happens?

8. The New Ordinary: The customer has experienced a positive transaction with you, and yet we’re just now getting to the really good stuff. This is a perfect time to prime them for repeat or upsell purchases or referrals. At this point, deliver content that aims at retention for recurring revenue products, and make savvy requests for direct referrals, testimonials, and word of mouth.

Of the eight, only Traveling the Road isn’t universal — if you’re an electrician, you show up and either fix the problem or don’t. But if you’re selling software-as-a-service, for example, content that gets users engaged with the platform is critical to reducing churn.

These core steps can provide you with a beginning framework for a detailed map of the buyer’s journey. The next step is to add the touchpoints that are unique to your product or service.

Finding When: Your unique journey map

You may be thinking about how exactly you’re supposed to map this out. Fortunately, there’s already an established procedure for this, just as during the who phase.

An experience map is a visual representation of the path a consumer takes — from beginning to end — with your content, and then with your product or service.

By mapping the journey, you know where the additional crucial touchpoints are, and what content can empower the journey to continue.

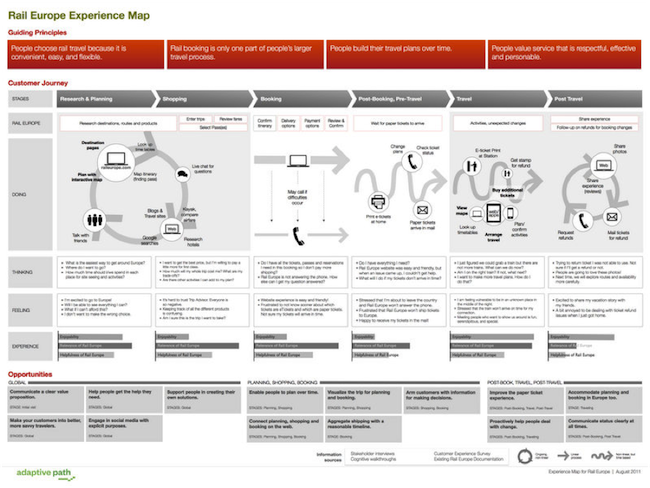

Here’s an example from Adaptive Path for Rail Europe:

This map demonstrates the journey a consumer would take while riding the trains in Europe. It follows her from the early stages of research and planning to the end of her trip.

You see what she is doing (searching Google, looking up timetables), what she is thinking during each action (do I have everything I need, and am I on the right train?), and what she is feeling (stressed: I’m about to leave the country and Rail Europe won’t answer the phone).

Do you see the correlation with the empathy mapping exercise you did back when developing a snapshot of your ideal customer? It’s no coincidence that we’re now applying what the prospect is “Thinking,” “Seeing,” “Doing,” and “Feeling” in their ordinary world to the journey they need to travel.

In a piece called the Anatomy of an Experience Map, Chris Risdon at Adaptive Path suggests your experience map should have these five components:

- The lens: This is how a particular person (or persona) views the journey. Keep in mind, this journey will not be the same for everyone. You will more than likely have more than one experience map.

- The journey model: This is the actual design of the map. If all goes well, it should render insight to answer questions like “What happens here? What’s important about this transition?”

- Qualitative insight: This is where the Thinking-Seeing-Doing-Feeling of an empathy map comes in handy.

- Quantitative information: This is data that brings attention to certain aspects of your map. It reveals information like “80 percent of people abandon the process at this touchpoint.”

- Takeaways: This is where the map earns its money. What are the conclusions? Opportunities? Threats to the system? Does it identify your strengths? Highlight your weaknesses?

You can find more detailed information on creating a customer experience map here. Like empathy mapping, it can be done solo, but works even better as a collaborative process, so that everyone on your team understands the journey from the perspective of the prospect and subsequent customer.

Mapping influential moments

Typical customer journey maps operate in terms of touchpoints within a process, such a travelers interacting with aspects of a train service. Meanwhile, storytellers focus on plot points — significant events that spin the action in another direction that keeps the narrative moving.

As content marketers, we need to instead think in terms of creating moments.

Moments of elevation, insight, connection, and pride. More than that, we want those moments to contain elements of influence that move the prospect closer to choosing us as a solution.

When you consider influential content, you may naturally think that it’s about how you present the information. While that’s true from an engagement standpoint, which principle of influence to apply and when to emphasize it is an exercise in what and when as well.

In other words, beyond the raw information of the what, you’ll also want to identify the order of emphasis (the when) for things like reciprocity, social proof, authority, liking, commitment and consistency, unity, and scarcity.

Every successful digital marketer I know purposefully applies those seven principles in their content and copy, because they all treat Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini as their bible. If you haven’t read it, you should — but in the meantime check out this six-page PDF that explains the original six principles, and here’s an article by Sonia Simone on the all-important 7th principle of unity.

At Rainmaker Digital, we think in terms of four different types of content when mapping the buyer’s journey. Keep in mind that great marketing content contains all of these elements; you’re simply selecting a category based on the primary aim of the individual piece at the appropriate time.

First up we have Attraction content, otherwise known as “top of funnel” information. This corresponds best with the Resistance to the Call point of the journey — it addresses the problem while also addressing common objections to moving forward. In addition to creating the feeling that “you’re reading their mind,” you’re also invoking early influence through reciprocity, social proof through share numbers, and establishing authority.

Next up, you have your cornerstone influence principle thanks to Authority content. The important thing is that you demonstrate authority, rather than claim it. Your Attraction content sets the stage, and your Authority content should be gated behind an email opt-in. At this stage, you’re establishing clear authority, continuing to leverage reciprocity and social proof, and adding liking, plus commitment and consistency thanks to the opt-in.

Affinity content solidly positions you as a “likable expert,” but it goes beyond that. This is where you let your core values shine. You reflect the prospect’s worldview back to them in a completely authentic way, prompting the powerful principle of unity. Never underestimate how often people choose to do business with people they like, and who also see the world like they do.

Finally, it all comes down to Action. Unlike Phil Connors, you don’t look for ultimate action at the beginning of the journey. But you do rely on smaller actions along the way, especially at the bridge between Attraction content and Authority content. That said, the key influence principle at this stage is scarcity, which you’ve earned the right to employ thanks to the other six principles. People fear missing out more than they desire gain, so make sure to use it ethically.

This is the outline of your story

It’s tempting at this point to try to imagine how you’re going to execute on your strategy, but you’re not quite there yet. For now, map the buying journey experience. In addition to your character, you’ve now got the plot points in the narrative you’re weaving.

All that’s left is to figure out how to tell the story. That’s up next time.